Don’t set New Year’s Resolutions. Use Design Thinking, Lean and Systems Thinking Instead.

New Year’s resolutions are declining in popularity — A Forbes survey showed that about 75% of people over 45 don’t bother with them anymore. And good riddance. Research shows that resolutions are not very effective at changing behaviors — after a month, nearly half of resolvers had failed at whatever they were resolving to do.

Resolutions are driven by what we think we should do

The top ten resolutions should look pretty familiar to you:

Exercise more, Lose weight, Get organized, Learn a new skill or hobby, Live life to the fullest, Save more money / spend less money, Quit smoking, Spend more time with family and friends, Travel more, Read more.

Most of these are driven by an idea of what we *should* look like, *should* have or *should* be like. Resolutions are driven from the outside.

Resolutions are also problematic because they are focused on the goal, devoid of any plan or process to make them happen. So let’s peel these two issues back to the heart of the matter: How to Reflect so you develop deep insights about how you want to be and How to Resolve so you accomplish what you want.

Reflect before you Resolve

Towards the end of 2020, I packed up my laptop, my sketchbooks from 2020, a mess of post-its and markers and loaded up my bicycle panniers. I took a 30 mile ride North up out of New York City to a quiet town in the woods. I booked a small AirBnb for myself and took a few days to think about the year.

I was exhausted from the emotional roller coaster that was 2020 and couldn’t really think about the new year. So all I knew was that I wanted to do a deep dive on the year that had just passed.

How to Reflect: Use a Process

There’s nothing wrong with randomness or improvisation in your reflection process…but even Improv has some fundamental rules with coherent internal logic. So I wanted to use a simple format to guide my process. Reflection is a conversation you have with yourself and I believe that we can, do and should design our conversations — both with others and ourselves.

I’ve found that the best processes have a deep, internal logic. That’s why I fell in love with Design Thinking more than a decade ago. Discover, Define, Develop and Deliver are four words that can move any creative conversation forward with clarity, regardless of the challenge. And Reflection is the perfect process to make the “Discover and Define” upfront part of the process effective.

Some of my favorite reflection prompts come in groups:

Plus/Delta is the simplest of all of the approaches I’ve used, and I learned it from Gamestorming, a powerful library of group process designs. Plus is positive and Delta is the symbol for change. This model of reflection asks us to ask ourselves “what worked?” and “what would you want to change?” . This simple process is a great reflection format because negativity is removed from the conversation — if there’s a “minus” we’re asked to turn it into a “delta”, which is a fundamental approach to reframing challenges.

Rose/Thorn/Bud (RTB)is attributed to the Boy Scouts of America. I first learned about this format from a co-worker of mine who used this format to facilitate a better dinner table conversation with his three daughters. He’d ask each of them for something nice that happened that day (A “rose”) and also would ask them for something not-so-nice that happened that day (A “thorn”). While Plus/Delta removes negativity on purpose, RTB includes it, on purpose. Knowing that negativity is included in the conversation can create clarity and safety. If you’ve ever seen the Pixar movie Inside Out you know how damaging it can be to focus only on the positive side of things.

“Buds” are like little roses…they’re not in full bloom, but they might develop into a rose with the right support. Buds can be something on the horizon, something emergent, something hopeful. A very simple way to put RTB is “Positive/Negative/Potential”.

Facts/Feelings/Insights/Potential: This approach has many mothers. A foundational approach in Non-Violent Communication (NVC) is separating out Observations, Feelings, Needs/Values, and Requests (OFNR). Disagreements in groups of people usually happen when we dance around and between each of these elements or combine them haphazardly. Using the OFNR approach as the foundation for a reflective process can be powerful, and it’s the approach I used for my personal retreat. The ONFR approach smells a lot like What/So What/Now What, another favorite for group reflections attributed to Rolfe et al in 2001.

Separating Facts and Feelings is powerful. The key reflection questions here are: “What Happened?” and “How did it Make me Feel?”

These two questions are extremely neutral, which is an advantage, but also very general. I use these two questions in my workshops often because I don’t want to put my thumb on the scale when teams are thinking. But looking with more specific detail can be helpful.

Positive/Negative/Potential is one more detailed way to look back over the year: What happened that was awesome? What happened that was awful? What happened that has potential? These questions address the first phase of the Design Thinking process to help us Discover “What Happened” in a more balanced way.

A friend recommended Alex Vermeer’s 8,760 Hours as a guide to my retreat. Vermeer’s approach is to do a mind map of 12 life areas: Values & Purpose, Contribution & Impact, Location & Tangibles, Money & Finances, Career & Work, Health & Fitness, Education & Skill Development, Social Life & Relationships, Emotions & Well-Being, Character & Identity, Productivity & Organization and (finally!) Adventure & Creativity.

Doing a RTB on *each* of these areas will give you a much clearer picture of “what happened” over the last year and a much deeper sense of how you feel about these elements of your life. If you don’t like Alex’s 12 life areas, choose your own or synthesize some other approaches.

Alex has his own suggested Reflection Questions for each element:

What went well?

What did not go well?

Where did you try hard?

Where did you not try hard enough?

By the end of a half-day, I had flipped through my sketchbooks for the last year and captured a series of nuggets of inspiration and sketched a host of mind maps for each area of my life. I was also beginning to feel energized about possibilities for 2021 (which surprised me).

Don’t Forget Gratitude

I talked over my plans for a retreat with my wife and my therapist and they both had the same advice: Don’t forget gratitude. Looking over the year (as difficult and chaotic as it was) and finding moments of brightness was profound. Gratitude and joy, in this context are data about how I felt. Many years back I diligently kept a gratitude journal: Three things I was grateful for, each evening. At the end of the year, I copied all of my entries to sticky notes and made a huge wall-sized map of what triggered gratitude for me. This map was a map to my happiness — it was pretty clear what elements I needed to keep cultivating in my life to keep me alive inside and out.

How to Resolve: Run Some Experiments

Using the “Discover” mindset from Design Thinking along with a series of thoughtful prompts can help you begin to “Define” what areas are most in need of support. Support to continue flourishing, and support to get on track.

Resolving to achieve ALL of the top ten resolutions will leave you pretty spread out and exhausted. You can’t Exercise more, Lose weight, Get organized, Learn a new skill or hobby, Live life to the fullest, Save more money / spend less money, Quit smoking, Spend more time with family and friends, Travel more, Read more ALL at the same time. So pick 2–3 areas from your reflection to work on.

So when I suggest “run some experiments” I mean SOME not all. Pick 2–3 areas from your reflection map and decide how you want to shift each of them.

Leverage Lean Startup for your Life experiments: Measure-Build-Learn

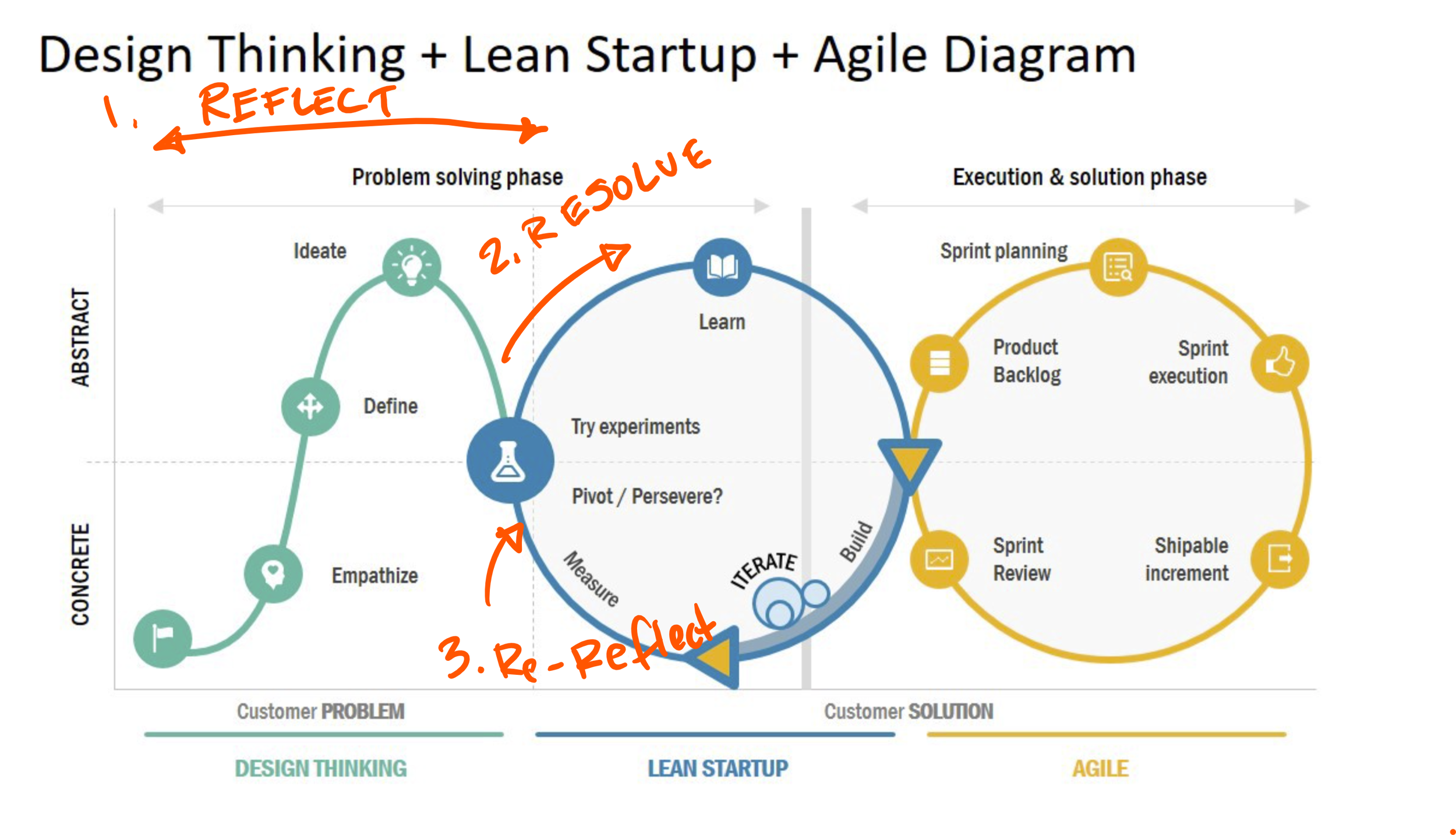

There are a lot of versions of this multi-circle diagram and they are all dizzying. The key idea is that there is a Design Thinking — Lean Startup handoff at the midpoint of the traditional double diamond, expanding and adding more detail to the “Develop/Deliver” phases.

We’ve leveraged a self-empathy process with our reflection questions to address the upfront, problem solving phase in the below diagram.

In the Lean mindset, you build as little as possible, try something out and then measure the results. We pick something we want to learn about, build something to help us do that, and measure the results.