Intelligent, well-informed people can look at the same data and reach completely different conclusions. That’s not a problem; that’s being human: we all tend to like our own way of thinking.

The problem is what happens next: when others don’t see what you see, often the natural impulse is to dig in, marshal your evidence, and start convincing people you’re right. Others on the team might do the same…and a “battle for who is right” ensues. Teams can get stuck there, for weeks or even months, infighting instead of moving forward.

Unfortunately, even if you win, the cost of victory might be higher than you think. Convincing others often backfires. In my experience, great leaders take other roads to real victory. Stop Trying to Convince People. Invite Real Alignment Instead.

When Winning Isn’t Winning

A client of mine, a C-suite leader at a fast-growing company, shared their experience with these “battles for who is right”:

“I’m always proven right in the end, but getting everyone there is painful.”

They had a sharp analysis, a clear strategy, and a track record of good calls. But each big decision with the team turned into a slog. Department heads dragged their feet. Peers pushed back. Meetings became battlegrounds.

My client was right and still miserable. The process felt draining, and frankly, a waste of time.

“There has to be another way!” they complained

So we set out to explore what the real options on the table could be.

The question that they came around to:

How could they be more convincing?

My ears perked up. I had an axe to grind about that word.

“I’m not sure that’s the real question,” I suggested.

“Getting people to go along with our ideas isn’t the same as agreeing on the best solution. For solutions to last, they require everyone’s participation, and that requires real alignment.

I think we need a better word than ‘convince’ for what you’re really trying to do.”

Sometimes, our struggles aren’t really about strategy—they’re about the language we use to approach one another.

So I took my client down an etymological rabbit hole…and you, dear reader, can come along. At the end, I promise you’ll have better strategies for inviting deeper team alignment at the ready for your next stuck meeting.

The Problem with Convincing: Words Create Worlds

Growing up, my folks would always make me look up any word I didn’t know - including its history and etymology - so my brother and I would know the deepest roots of words.

Understanding the layers behind the words we use can help us understand what kind of worlds we’re creating when we use them.

So, what kind of world are you creating when you seek to convince someone?

Problem One: Convincing means a winner and a loser. And losing sucks.

Convince comes from the Latin root vincere, from which we get our English word “victory”. Convincing pulls from its linguistic roots - we seek to “conquer” or “subdue an opponent through strength.” You can see this Latin word at work in the famous saying attributed to Julius Caesar, “Veni, vidi, vici,” which he apparently wrote in a letter to the Roman Senate after a swift war victory. The translation: “I came, I saw, I conquered.”

When I hear the word “convince,” I hear someone who wants to win. It feels good to stand above your opponents and have them admit defeat. To beg for mercy!

Wanting to win can often lead us to lose empathy with the other folks in the conversation. And in the heat of that emotional intensity, when we lose our empathy, we can forget how hard and painful it can be to be on the losing side of an argument.

Problem Two: Convincing creates opposition

A victory implies a battle, a struggle for supremacy. A battle also implies two opposing sides.

When you set out to convince, you make the conversation into a battle to be won and lost. You bring force and, as Newton’s laws of motion tell us, force creates counter-force. You’re creating resistance before you’ve even finished your argument.

Winning means that in the end, we will just have one side (our own!). We want that unity of opinion, but we create opposition in the process.

“Is that the kind of environment you want to create in conversations with your stakeholders?” I asked my client.

My client reflected and replied: “No. I want the solution to be one we all believe in. “Every time I win an argument, I feel the cost in trust the next day.”

“The act of convincing turns your colleagues into combatants. It subtly signals, I’m right; you’re wrong. What’s a better word for what you’re really trying to create?”

What Listening Does That Convincing Never Can

The first tool to reach for when there’s a brewing battle in your team isn’t more facts and better arguments - it’s listening to them more deeply.

Listening deeply to others’ perspectives will still the storm of disagreement.

Recently, I hosted a team offsite for a senior leadership team wading through deep factions, lots of tension, and plenty of resentment.

After we spent some time building more connective tissue of trust and mutual understanding, I introduced a structured listening exercise where pairs took turns: one person spoke for a few minutes about a difficult issue. Not just the story, but also sharing their feelings and needs. The other person was tasked with listening and reflecting back what they heard. No fixing, no counterpoint, just listening. Which is harder than it sounds.

The moment of completion came when the speaker’s shoulders dropped. They would take a breath. Over and over again, the speakers showed the team, with their whole bodies, the feeling that I’ve been heard.

No one had to agree. But something shifted.

If you want to try this at home or at work, a version of this approach is drawn from the Listening Triangle - a mental model I use to teach teams deep active listening. Read more here.

Listening does more than convincing ever can. In the deep listening process, the listener can learn where a path forward might exist - based on what the person on “the other side” really cares about.

Finding a path forward is where the leadership team ended their offsite - with an offramp from the resentment into empathy and seeing an opportunity for collaboration.

Your homework: Leverage Listening as a Leadership Move to Diffuse Opposition

The next time you feel the tension of opposition and the desire to convince, listen more instead.

Ask, “Can you tell me when you started thinking about this that way?”

And repeat back what they tell you and ask, “Is there more?”

Often, there is a fear that understanding their position will make you lose your grip on your own. And you might! But you’ll also understand their position deeply enough to find where they might be open to creating what you really want.

Leveraging intentional curiosity, listening deeply even when you feel there is no point, can help ensure that you don’t merely assume you understand their beliefs about the situation—or even that you agree on what the “situation” is exactly. Deep listening allows people to surprise you and tell you more.

That simple shift turns opposition into curiosity, and curiosity into collaboration.

What are we each protecting?

In tense conversations, we think we’re arguing about facts or strategy. But beneath the surface, we’re usually protecting different things:

One leader protects revenue.

Another protects culture.

Another protects people.

Another protects the brand.

When you don’t know what someone is protecting, every debate becomes a tug-of-war. But once you understand what’s sacred to them, you can align around shared protection instead of competing priorities.

During that same offsite, I asked each leader, thinking about a key conflict on the leadership team: “What are you bound to protect in this decision?"

Once they named it out loud, the tension eased. The argument about “what to do” turned into a conversation about “what matters most.”

New Words create new worlds

Language shapes behavior. The words we choose quietly program the energy we bring to our work. So it’s worth looking closely at the words leaders use to describe how they move others.

Convince, again, comes from vincere, to conquer. You win; they lose.

Some options that bring different energy to the process of alignment:

Persuade derives from the Proto-Indo-European root swād, meaning “sweet” or “pleasant”. You sweeten the deal to get agreement, which means you might seek to know what that sweetener could look like for others.

Influence from the Latin fluere, to flow. You move things through attraction, not pressure. Flow happens like water down a hill, naturally and obviously. How can you see where the team wants to flow?

Invite — from invitare, to call in or challenge, with the Proto-Indo-European root gwei, which means to “go after with vigor, to pursue.” You ask others to join a shared pursuit. We call them in, not out.

Sharing these words with my client, I asked them to consider a few things:

Which one created the conditions for deeper change?

Which one could help them be the leader that they want to be?

Which word gave them more of the energy they craved?

Invite was an easy answer. There’s a reason I put “Invitation” at the top center of the Conversation OS Canvas in my book Good Talk, about how to design conversations that matter.

Any word we choose implies a different kind of leadership energy and becomes a design principle, guiding light for how we approach our leadership conversations.

Convincing conquers.

Persuasion sweetens.

Influence creates flows.

Invitation engages.

Which one creates the conditions you want in your team?

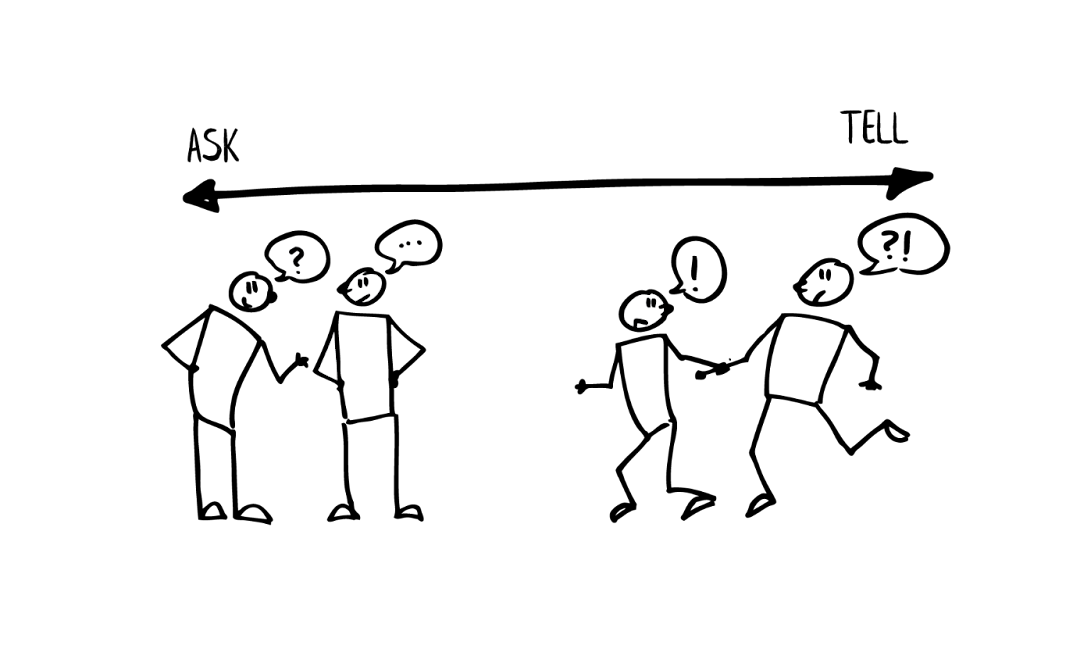

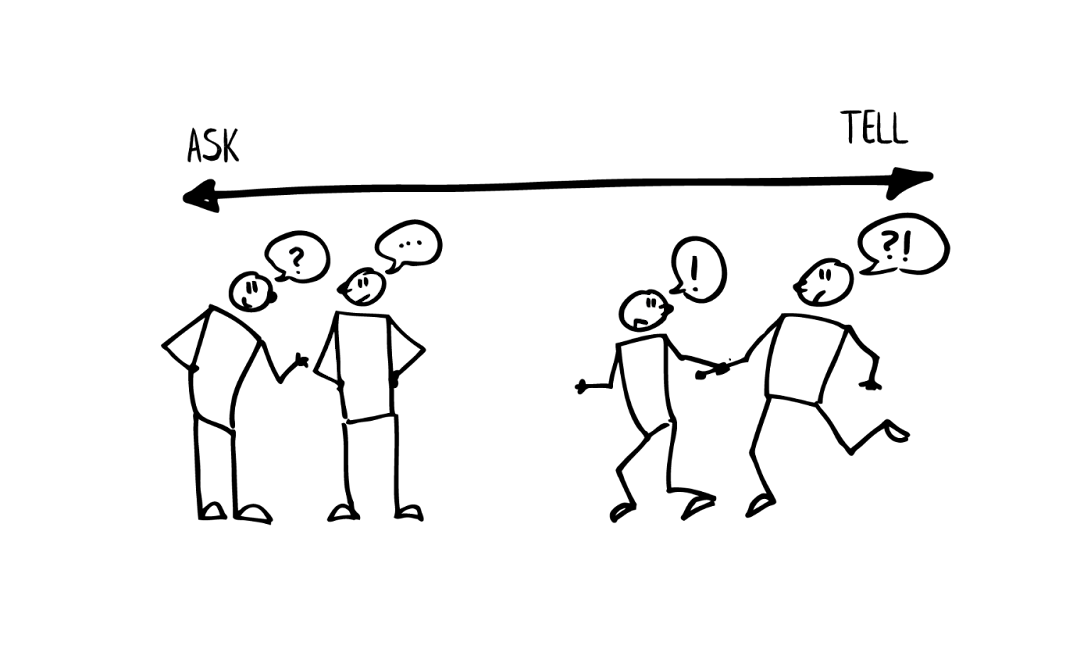

Tell Less. Ask More.

Edgar Schein called this shift “Humble Inquiry.”

When you tell people what the problem is, you drag them toward your conclusion. They might comply, but they don’t commit. Telling is like pushing them to your side, forcing compliance, and shutting down choice.

If you ask them what problem they see instead, you draw them in. You invite them to co-create the definition of the problem, which means they have ownership in the solution.

Asking feels more like a magnetic pull.

Next time you feel tempted to prove your point, try these linguistic pivots:

Ask: “What are you seeing that I might be missing?”

Reflect: “So it sounds like you feel that X is important to protect here. Did I get that right?”

Invite: “What could an experiment to test out our assumptions look like?”

These small linguistic pivots transform power dynamics. It shifts you from commander to collaborator, and can get your team out of argument and into experimentation and action.

The Practice of Inviting Alignment

Here’s what I often coach leaders to practice:

Notice when you’re convincing. The physical cues are familiar — faster speech, tighter jaw, more evidence.

Pause for perspective. Ask yourself, “What am I protecting right now?”

Shift to Invite their story. “Tell me what’s important to you here.”

Listen until the shoulders drop. That’s your sign you’ve reached that critical "I've been heard" feeling.

Co-author the next step. “What could we each do to protect what matters most?”

These are simple moves, but they require presence — and courage. Inviting alignment means giving up control of the outcome long enough to let something better emerge.

The Invitation at the Heart of Leadership

One of my favorite lines from poet David Whyte says:

“A real conversation always contains an invitation. You are inviting another person to reveal who they are or what they want.”

Convincing tries to change minds. Invitation changes relationships.

You can’t force people into alignment; you can only create the space for it to arise.

So before your next high-stakes meeting or debate, pause and ask:

What invitation could I pose that would help others think differently about this challenge?

That question — asked sincerely — might be the start of the alignment you’ve been trying so hard to convince people into.

If you’re looking for better questions to lead your team conversations more powerfully, check out my essay about these three essential leadership conversations for creative transformation.