Performance vs. Preparation

Even the best actors spend more time rehearsing than performing. The same is true for athletes. For Olympic athletes, they train a whole year for just a few days of all-out performance! In general, no athlete trains 8 hours a day, five days a week. And coaches are always on hand in both cases to help guide top performers through their training and preparation and help them reflect on past performance.

For CEOs, it’s flipped - most of their time is spent “on stage” - in calls with investors, meeting with team members, having one high-stakes conversation after another. And leadership can feel lonely - often, they are doing it with less support than they need. Everyone needs to go backstage to recover and prepare for the next act from time to time, and leaders in particular can significantly benefit from an intentional approach to their development and performance.

As an executive coach to CEOs and their C-suite teams, I help leaders actively and intentionally practice for high-stakes scenarios - tough negotiations, sensitive one-on-ones, or a strategic conversation about pivoting with investors. Together, we reflect on past performance and clarify strategic intentions for the future. Just like in the gym, doing all of this with a supportive coach can make the process more focused, accountable, and effective.

I often tell my clients that they are their best coach. In fact, they are the head coach. I’m just the assistant coach. And wouldn’t you know it? Most of their self-coaching happens in their heads: after all, our toughest conversations are usually with ourselves. Our inner conversations either help us or hold us back. The following seven questions are starting points for worthwhile conversations to have with yourself. Asking yourself these seven questions can help you clarify and solidify your leadership stance.

Using these questions can help you find clarity in the chaos, be more purposeful in your leadership, and keep an eye on your strategic intentions…all of which will help you accelerate your growth and the growth of your company and team. Think of every minute spent with these questions as training your most crucial leadership muscles.

The Seven Self-Coaching Questions

Here’s the TL;DR:

Spend 10 minutes journaling with a pen and paper on any of these questions the next time you feel stuck or turned around, and notice what shifts.

How am I spending my time?

What gives me energy?

Who are my heroes and teachers?

What will happen if…?

What will having that make possible?

What do I really, really want?

How have I been complicit in creating what I say I don’t want?

If you like knowing the why behind the how, here’s a deeper dive:

The Power of Self-Coaching Questions

The basic function of an executive coach is to ask questions, to listen, and to help create clarity. A coach is not there to give answers or advice (that’s a mentor or a consultant), but I will often ask as many questions as needed to help you get to the heart of the matter.

You have that same power to ask yourself impactful questions, too.

The questions that I return to again and again are ones that help leaders with the perennial challenges of leadership:

Making high-stakes decisions in high-ambiguity situations

Spending time on high-impact, high joy work

Clarifying goals

Reframing challenges as opportunities

Making Leadership Values crystal clear

Questions are like portals - they open up new doors, new pathways of thinking. “Question” has the word “Quest” in it…and Questions are like that - they can be journeys or adventures. Leadership is a Quest after all - a quest to create something great.

So it’s a simple equation - ask yourself better questions, get better answers.

How to Use These Questions

First, I highly encourage you to use pen and paper, set a timer, and write your response to one question.

Writing slows down thought, from thousands of words per minute circling in your head to twenty clear, coherent words per minute on paper.

Going for a walk and talking to yourself (150 words per minute) can also help slow down and clarify your thinking - especially if you transcribe the audio and read it later.

But handwriting is almost like biofeedback. Seeing and hearing your words form on paper as you write can be grounding and meditative, and helps shift your brain functions in similarly positive ways.

Many of my clients make journaling a regular practice because it reliably shifts them from chaos to clarity.

The Why Behind the Seven Self-Coaching Questions

1. How am I spending my time?

It’s the job of a CEO to spend (ideally) 80% of their time on strategic efforts that create impact. As per the Pareto Principle, that time ought to be focused on the 20% of activities that will create an outsized impact. If you’re spending all of your time chasing waterfalls or shiny objects, you might not get as much traction or impact.

Conducting a time audit by looking at data from a few actual weeks is best.

Look at that data and ask yourself:

Which of these hours is aligned with the impact I intended?

Which of these hours were not aligned with creating outsized impact?

How am I using my time to actively care for and support myself?

Looking at the real data can be sobering because there is usually a mismatch between our intentions, plans, and reality. That last question about self-care is key, because there’s no way you can do the job you need to do without making time for sleep or support. Every top athlete spends a shocking amount of time stretching and icing, and resting.

2. What gives me energy?

And it’s worth going a layer deeper - which activities are giving me energy and which are draining my energy? Leaders who learn to eliminate, automate, delegate, or redesign draining tasks free up extraordinary capacity. If we’re spending our time on activities that create joy or energy for us, we can do more in a day.

How are you spending your time?

Right now, set a timer for 3 minutes and list everything you did yesterday. Maybe even open up your calendar if you can’t remember.

Circle the top 2 things that gave you energy.

What’s one thing you could eliminate, automate, or delegate?

These questions actually take a bit more homework than a 3 or 10-minute journaling sprint. Use this Time & Energy Audit document to get started. Doing this with a coach can add a layer of accountability and clarity, but I always ask my clients to do their own audit first.

3. Who are my heroes and teachers?

Marcus Aurelius starts his 167AD classic Meditations with a list of his teachers and what he learned from them. Making a list of your heroes and teachers can be a powerful exercise.

(Stop for a moment and write them down now! I bet a few folks have already appeared in your mind.)

Who do you admire in your field, in your life, in history? These don’t need to be people you’ve met - I’ve never met Socrates, but he’s been one of my heroes and teachers since I was 13.

Now…ask yourself: why? What qualities do they express naturally that you admire? This list is a set of characteristics that you value. And you need to know your values as a leader - those qualities guide you in difficult times.

Don’t forget the essential truth - if you spot it, you got it. You admire these qualities, these values, not because they are out of your reach, but because they are inside of you. Narrow those values down to 3-5, make sure you write them down somewhere visible, and make sure you reflect back on them regularly. (Many thanks to Ayse Birsel for reminding me of the power of this question.)

4. What will happen if…?

Often, when people have a tough decision, they arrive at one or two options quickly and then circle around the pros and cons until time runs out.

Instead, try this four-part reframe to expand your vision.

What will happen if…I do X?

What will happen if… I don’t do X?

What won’t happen if… I don’t do X?

What won’t happen if… I do X?

Most leaders making difficult decisions need to weigh the outcomes of action or inaction. And they do this in situations of high ambiguity - there’s no clear, easy answer. Scenario planning is a core leadership skill…and it’s invaluable to consider several opposing scenarios. These questions present four unique ways of looking at your choices and their outcomes.

One CEO I was working with was really tired. After more than a decade and millions of dollars raised, the company hadn’t really found true traction, even with celebrity backing and doing all the right things. He was ready to quit. When he found a potential acqui-hire that would allow him time with his family and time to tinker with other ideas, he still felt stuck - what would his investors think? What about his relationships with his investors? Was he failing as a CEO if he quit before his IPO? These four questions helped him feel fully aligned on his next step - All in.

Try out this question set the next time you’re weighing a key hire or a strategic pivot, or even considering how to spend your time - going to an event, or on a trip.

5. What will having that make possible?

As we weigh a course of action, we’re often fixated on the near-term result - the goal or objective.

It’s good to step back from our goals and ask…and then what? Look at the bigger picture, the longer arc: What will having that goal mean? What’s the goal after the goal? As my wise mother likes to say, “the ceiling becomes the floor.” That is, when we grow and evolve, each achievement resets the baseline. Looking from the vantage point of the future, where our goal is achieved, what is true? Who do we get to be? What is next?

This question helps align goals with a larger vision, not just short-term milestones.

6. What do I really, really want?

I call this “The Spice Girls Question”. Akin to the activity 9 Whys, I often take time to peel back the layers of the onion on a goal a client has.

Why do you want what you say you want? And why that?

Keep asking until you reach the deepest desire.

We’re trying to get to the biggest goal, following the ladder of abstraction to the top.

I want to learn: Is the goal theirs? Or is it based on an idea of the kind of person someone else wants them to be, borrowed from someone else’s expectations?

What goal is aligned with their essence? Their values? The kind of life they really want to live?

Real leadership comes from pursuing goals aligned with your essence and values, not external pressure.

7. How have I been complicit in creating what I say I don’t want?

I learned this question from Master Coach Jerry Colonna during our podcast conversation.

When we’re in the thick of a challenge, this question is a powerful one to slow the conversation down and look at what’s in our zone of control.

In these moments, it’s easy to look outwards. When sales are stalling, when the team is going off the rails, it’s common to look for “one neck to wring” - the source of all the problems.

Making a list of everything that’s getting between us and what we want to create might include external factors - the market, the funding environment, or someone else’s attitudes and prejudices. But that puts the locus of control outside of us. When everything is someone else’s fault, there’s nothing we can do on our own about the situation. We can try to fix others, but there’s a limit to what’s in our direct control.

Step back and ask:

What am I doing to make this happen? Or to keep it happening?

What is in my power that can make a difference?

How have I been complicit in creating, allowing, or promoting this situation that I say I don’t want?

If you’re not part of the problem, you can’t be part of the solution, as I learned from my podcast conversation with author Adam Kahane. Most problems are systems problems - rooted in complex contexts. A simple solution is usually hard to find. If you have one, guess again. You, dear reader, are part of the system. So, you can find something, however small, that you can do to make a shift in the situation. And sometimes that shift happens inside - not what you do, but how you think or feel about the situation.

A COO I worked with realized they were caught in a “hero” role—constantly rescuing the team from a CEO they saw as problematic. They were caught in a drama triangle.

Wherever there is heroic behavior, there is a villain and a victim. The cycle always repeated: avoidance, then confrontation, then back to rescuing. With some deeper reflection, we uncovered how good it felt to be the hero, and they were able to see their complicity in the pattern. Looking at their complicity helped them step back and have a cool and clear conversation with the CEO about the facts and impacts of the situation before a flare-up.

Take a quick scan for a stuck conflict in your work or life. If you’re pointing a finger in blame at the other person or party, pause and ask: ‘How might I be contributing to this?’

Point the finger fully back at yourself, just for a moment. If the situation were 100% your fault, what would that make possible for you? It can feel uncomfortable assuming 100% responsibility. More likely it’s a combination of factors netting out to some ratio or another…but there’s always a gift to be found in assuming 100%. After all, if the situation is 100% your fault, the solution is 100% in your power!

The Power of Telling Someone

Speaking or writing your answers to these questions will absolutely have an impact. Spending time with them can unlock new levels of clarity, purpose, and resilience in your leadership. You could even tell an AI your answers and ask for feedback. But there is something powerful about telling your responses to a real human who cares about you and what you are trying to create and accomplish in the world and in your life.

There’s a reason leadership can be lonely - it’s hard to find someone you can really tell everything and anything to. You can’t complain about your co-founder to your romantic partner indefinitely. You can’t vent about your CTO to your VC without it having potential impacts.

Working with a coach can make space for deeper conversations; I don’t accept easy answers and hold my clients accountable to their biggest dreams. What could you accomplish with someone in your corner who was 100% dedicated to your success? When you’re ready to invest in a partner in your growth journey, please reach out here. While I only serve a few clients at a time, I’d love the opportunity to explore if working together would be a good fit.

PS - For the nerds

I did some digging to find actual numbers on training volume for top athletes and found this fun small study from High North, a sports coaching firm.

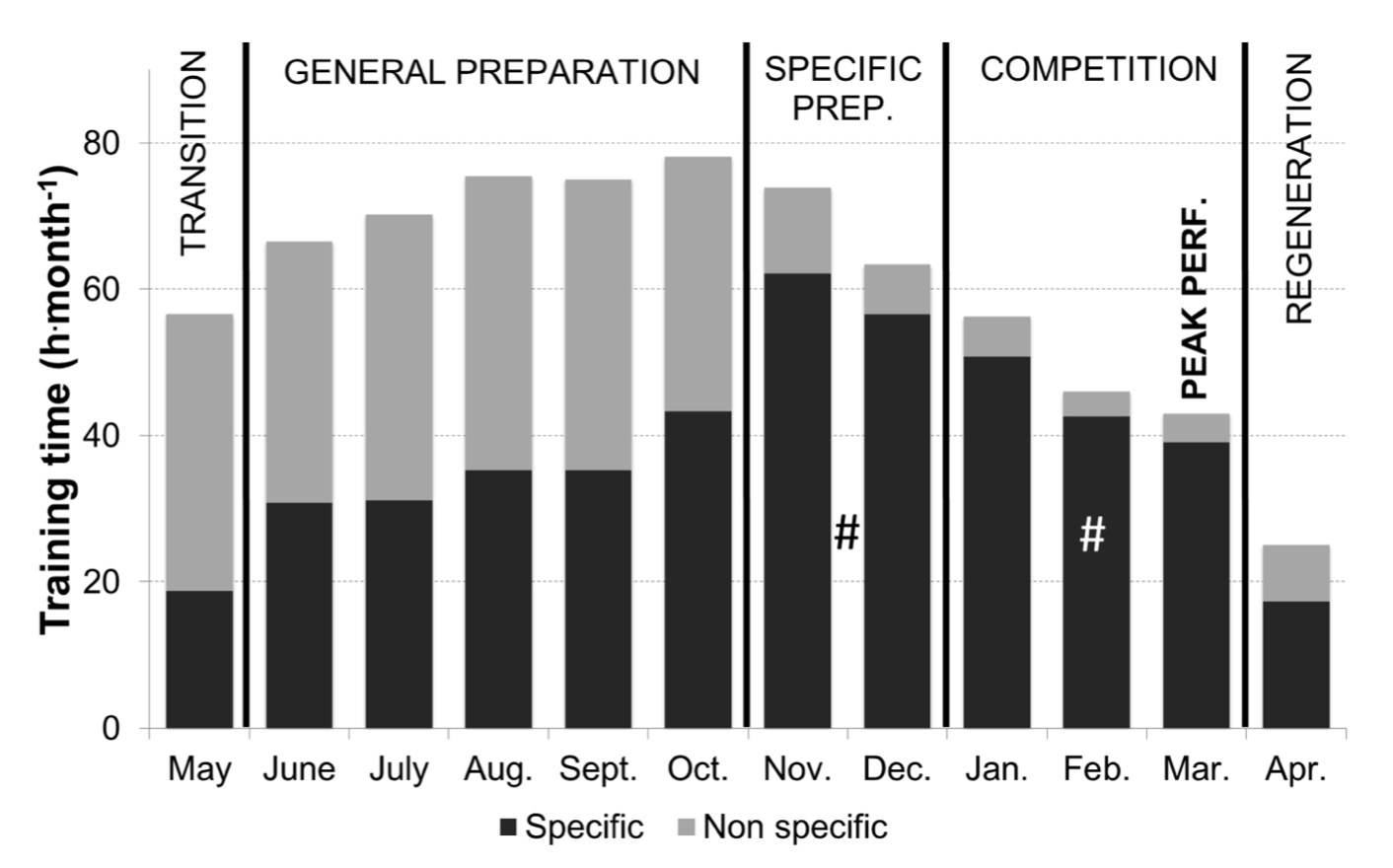

I particularly enjoyed this chart, which maps training time per month for Olympic athletes. Notice the shift from general conditioning towards more specific sport-related training as the competition approaches…and that total training volume decreases as competition approaches!

Also, 80 hours PER MONTH is the max amount of training volume. With 480 waking hours a month, that’s spending LESS than 20% of their time a month in training - around 3 hours a day on average.

So here’s a bonus couple of questions for your time audit:

What would your day look like with 3 hours of solid impact?

What would you do with the rest of your time?